Avoid Invasives

The Low-down on Invasive Species

Invasive species pose major threats to New York’s biodiversity, and without biodiversity, we risk losing everything, from the variety of bird life and the health of native trees to most of our wildflowers and our own health. The whole countryside would be overwhelmed with strangling vines, bushes full of thorns that bear no fruit, and a single species of tree that turns a forest into a fake-looking, monotonous backdrop. Pollinators will give up and move a more welcoming state, like Vermont.

Invasives—the term is so polite it’s almost a euphemism. They come from far away, usually Europe or Asia, brought carelessly or inadvertently. Sometimes all it takes is a seed. Back home they are restrained by their native biodiversity: Other species eat them or overshade their growth. Here, literally, it’s the New World. Invasives are pirates among peasants, Visigoths among vinologists. They have no enemies or rivals. There is plenty to eat, room to grow, an environment to dominate, and the climate is great. A somewhat arbitrary rogue’s gallery: Emerald Ash Borer, Garlic Mustard, Multiflora Rose, Eurasian Watermilfoil, Japanese Knotweed, Mile-a-Minute creeper/sprinter, Swallow-Wort (Black and Pale), Purple Loosestrife, Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, Viburnum Leaf Beetle. There are, unfortunately, many more.

The best way to not enable invasive species is . . . don’t plant them. If you have one, get rid of it fast, and every root. Don’t plant species on the PROHIBITED PLANT LIST. When developing new areas, remove existing invasives and incorporate native plants

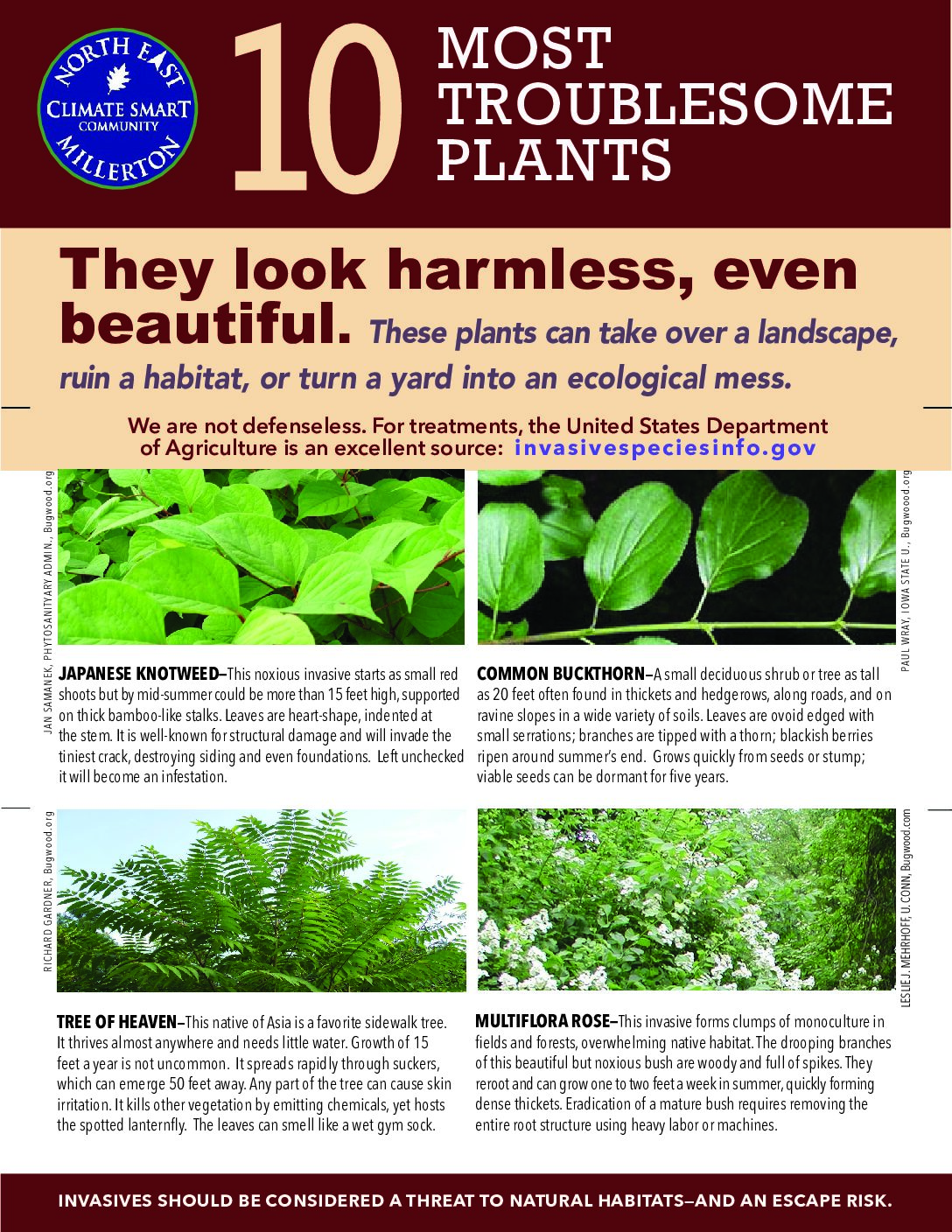

Click image to download our “10 Most Troublesome Plants” brochure.

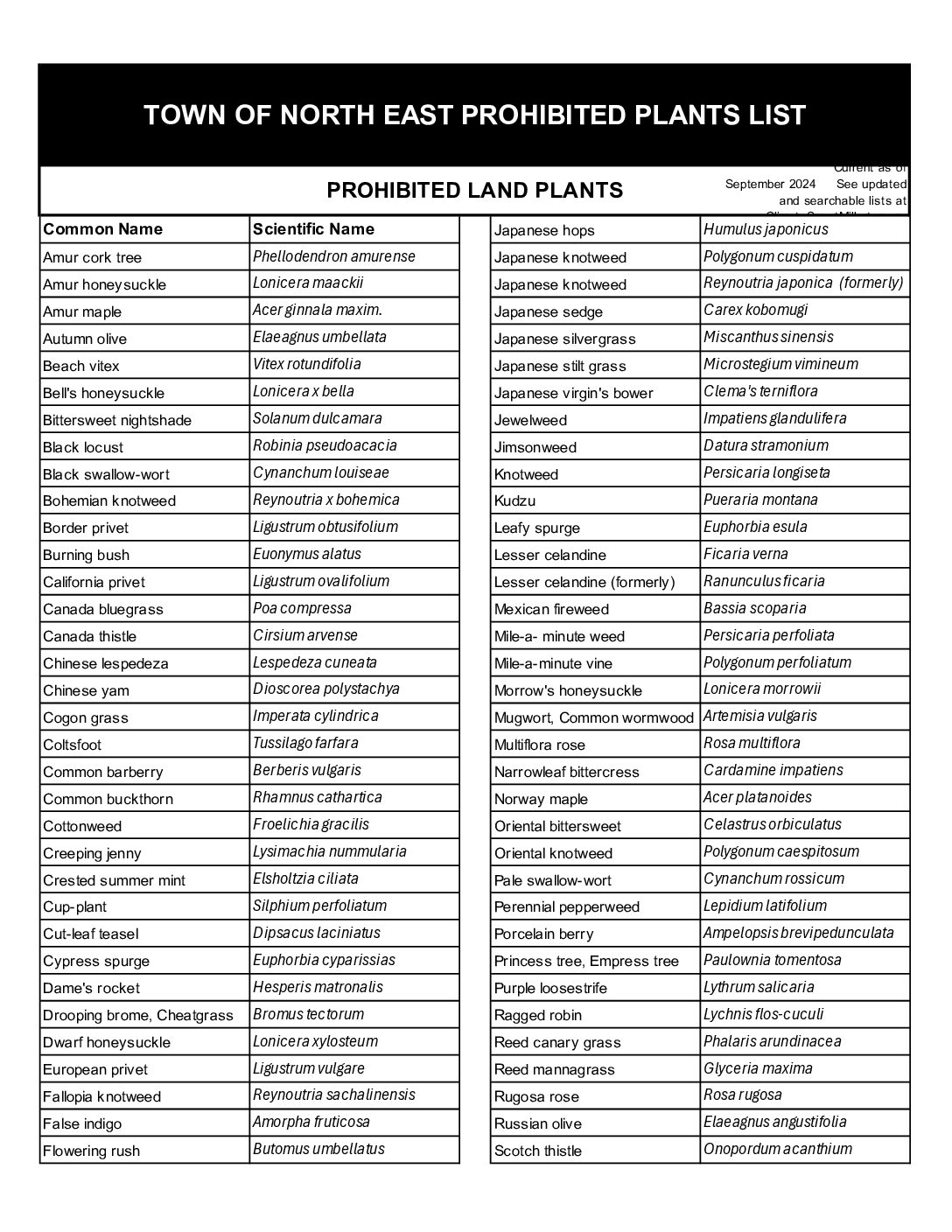

Avoid plants from our “Prohibited Plant List”. Click to download the flyer or searchable spreadsheet

Plant Natives

Native Species

Native plants are species that naturally occur in a specific geographic region, having evolved and adapted to the local climate, soil, and other environmental conditions over a long period. They are an integral part of the Local Ecoregion and have co-evolved with native wildlife, forming complex relationships over time. Natives are crucial for supporting the whole food web, providing essential food and habitat for wildlife, and helping to maintain biodiversity. They also offer “eco system services”: environmental benefits such as reducing water runoff, preventing erosion, and improving air quality. Additionally, native plants often require less maintenance and are more resilient to changing local conditions than non-native species.

RICH STALZER

RICH STALZER

The Pollinator Garden in Millerton next to the Post Office is planted exclusively with native species.

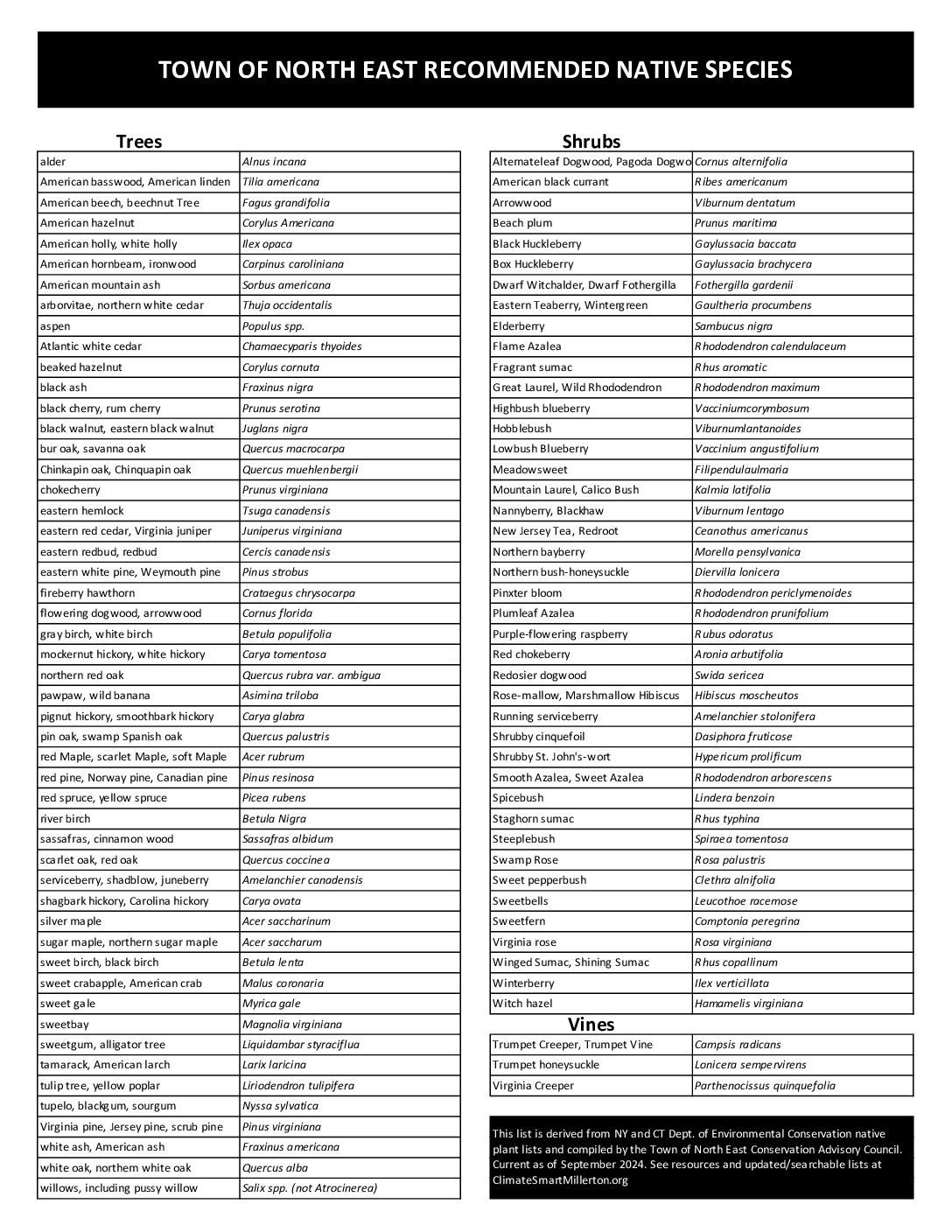

Click to download brochure or searchable spreadsheet.

Keep Our Skies Dark

Did you know: Light Pollution causes serious ecological harm!

Excessive lighting is a recognized hazard for many species, including migratory birds, pollinators, and mammals, including humans. Many animals rely on the light of the sun and the moon to orient themselves as they move about the world. Artificial light can confuse these instincts that were formed over the course of millions of years and as a result our biodiversity suffers.

- Turn off your outdoor lights when they’re not needed. Motion detectors and timers can help reduce light pollution.

- Direct light where it’s most useful. Lights should be aimed towards areas that enhance nighttime safety, for example towards the ground at walking paths

- Use “Warm” color lights. LED light bulbs come in a range of colors ranging from “warm” to “daylight”. Warm lights, with a 2700k color index are the least harmful.

Plant A Tree

A Big Idea: Put Something in the Ground

There is one simple act everyone can do that guarantees a reduction of carbon in the atmosphere and helps a local ecosystem in multiple ways without question.

Plant a tree. Just plant a tree. Or plant two trees. Or plant as many as you want, but just plant a tree. Get your friends, family, and co-workers to plant a tree. Trees are one of the definite answers to the question. The benefits of planting trees are almost too numerous to mention. To name a few: they absorb carbon dioxide, release oxygen, increase property values, reduce rainwater runoff that causes soil erosion, buffer noise pollution, cool your home, streets, and communities, and they can reduce stress, lower blood pressure, and improve one’s mood.

The type of tree you plant depends on what pleasures you want the tree to offer. If you want to see blossoms in spring plant a flowering dogwood, crab apple, or red bud. A fruit-bearing tree like pear or cherry have beautiful blossoms with the added benefit of fruit for pies which is always a good thing.

One thing to consider: The warming climate is affecting what trees thrive in which latitude. Here, The current mix of maple, beech, and birch, forest biologists note, is already shifting northward, and the oak and hickory forests south of us are headed our way. If you are thinking beyond the next 20 years or so, consider planting the hardwoods to come rather than trees that might do less well in higher heat, avoid trees known for easily broken limbs, and get good advice about any conifer.

But please don’t plant an invasive, defined as a tree that triumphs over native plants, doesn’t support local wildlife with anything they are used to eating, diminishing biodiversity, and may harm the environment. These include quite a list, from Norway maple, Ailanthus (tree of heaven), Callery pear, Amur maple, Amur Corktree, Common Buckthorn, Glossy Buckthorn, Black Locust, Box Elder, Quaking Aspen, Russian Aspen, Tamarisk, and White or Sliver Poplar. Use a reputable nursery. It either won’t sell these trees or will label them as invasive. For more information, google invasive trees or visit these sites:

- Wikipedia – List of invasive plant species in New York

- The Morton Arboretum – Invasive trees and plants

- The Spruce – 20 invasive trees

Maybe you are just starting a family and want to plant a sapling and watch it grow with your young kids. The tree becomes indelibly tied to you, your family, and your memories.

Maybe you want to provide a flowering tree for pollinators, or a conifer for a patch of green to relieve the unremitting grays and browns of winter. Maybe a large shade tree that the kids can climb, you can put a swing on, and that feeds the critters. An oak tree or native maple would be a good choice.

Whatever you want from a tree, there is one for you. And, for many years to come, you’ll be doing a little something to combat global warming. Just plant a tree.

Help Millerton Add Trees to Its New Park

Millerton’s major public park and primary recreation area, Eddie Collins Memorial Park, is receiving a multimillion-dollar upgrade. Work is underway. A big part is planting a mix of one hundred hardwood and flowering trees, starting with saplings 3 to 4 inches in diameter. As they grow they will help clean our air, cool the park in hot weather, nourish and protect birds, insects, and wildlife, and adapt the area to climate change.

These trees need your help! This is a community effort. Please donate what you can. For more information and to donate, go here: millertonpark.org/trees.

Hickory tree; the species is moving north due to climate warming.

POTTER HAMSTRA

POTTER HAMSTRA

Local Red Oak in late October, after leaves have turned from green.

Looking After Your Land For Posterity

We do not inherit the land from our ancestors, but borrow it from our children. —Native American saying

Learn Your Land

In June 2020 Cornell Cooperative Extension of Dutchess County organized a series by regional experts about the environmental stewardship of properties and natural areas. Called “Learn Your Land,” this excellent series of three two-hour sessions is intensive and well worth it. Its presentation slides are available for download.

The series will help understand how to:

- Inventory the natural resources on your property or community

- Learn proven management and conservation strategies

- Develop plans to implement best management practices

RICH STALZER

RICH STALZER

Productive agriculture land and open space, two features of our area, will be increasingly valuable in the coming years.

Volunteer

Give And Ye Shall Receive

Most of us have a personal connection to the nature around us we could act on, to the benefit of our surroundings, our community, and ourselves. We just need an idea and a nudge. “For it is in giving that we receive,” said Francis of Assisi, patron saint of animals and the natural world. The dynamic of giving and receiving, receiving and giving has been life-sustaining for many.

If you’re self-motivated, don’t need help or structure or mutual support, here are some starter ideas.

- Plant a tree and tend it, make sure it’s watered, protected, and free of vines until it’s twice your height. Then plant another. Find saplings at the edge of a woods or from the Cornell Cooperative Extension in Millbrook every spring.

- Tend a garden—your own or someone else’s, such as a neighbor who no longer gets around comfortably and would be grateful for some weeding now and then.

- Eradicate an invasive. Chances are better than fair that no one will stop you.

- Care for animals at a local shelter, an animal rescue group, or the Humane Society (humanesociety.org/volunteer).

- If you’ve got leadership skills, start an organization. Every community needs something. Identify that need and put a group together to address it. There tend to be more followers than leaders.

- Build a bridge—not literally (unless you’re a civil engineer), but between groups that would benefit from a little cross-fertilization, or that don’t get along but should.

- Help someone write an article or a letter to the editor, to an office holder, to a friend.

Volunteers trimming growth in early spring along the Harlem Valley Rail Trail.

Climate Action

Climate Urgency, Ideas, and Channels for Action

It must be clear by now that our climate is headed in the wrong direction. This is largely the fault of human activity, human desires, and human ambitions. It must also be clear that many people don’t understand the issue in any meaningful way, many others are happy to deny the evidence of their senses, and not a few are dug into a position rooted in oil-fueled prosperity and the American sublime that admits no alternative—all others are traitorous.

Weirdly, we’re talking about a critical scientific certainty: survival of the human race and quite a lot of the planet’s biota along with us. You’d think that would sink in, here several centuries into the Age of Enlightenment. When the earth finally breaks through to the other side of carbon surfeit, 500 or 5,000 years from now, it will have vastly different, much less sophisticated biodiversity—very likely a giant step backward, with homo, no sapiens.