Town Bulk Trash Day

Get rid of your unwanted, unusable big stuff the right way and free up space at home

Bulk Trash Day is held seasonally at the old Town Garage on South Center Street for residents of North East and Millerton. You drop it off, Climate Smart volunteers will take care of the rest, making sure that it is recycled, repurposed for further use, or properly disposed of. At certain events electronics and tires are accepted. You are charged a modest fee based on the quantity of discardables you leave, which helps the Town defray the costs of using the dumpsters. Cash only, please.

The fees collected cover the dumpster costs so the event breaks about even, leaving two beneficiaries who were enormously grateful: The environment and less cluttered households throughout North East.

Bob Stevens, head of North East’s Highway Department, at the controls of a much needed front-end loader.

The 2020 North East Town Bulk Trash Day collected enough electronic waste to fill two pickup trucks.

Plastic Bags

The Solution Is At Your Fingertips

Sometimes progress is ill-advised. We used to carry stuff in all sorts of containers. Then in 1965 a Swedish engineer invented the plastic shopping bag. It came to the US 1979 and hit the big time thanks to Safeway and Kroger.

Part of the problem with single-use plastic bags is that they often escape the waste stream. HDPE or high-density polyethylene (plastic #2) bags litter roadsides, cling to trees and bushes, clog countless mechanical orifices, block storm drains, and spread their environmental havoc over centuries. To make more we keep pumping fossil fuel from the ground.

MOTHER EARTH NEWS

MOTHER EARTH NEWS

Food Waste

Food In The U.S. Seems Cheap, Until You Factor In Production And Waste

Food waste makes its own significant contribution to the climate crisis, and on hard-pressed household budgets. Some of this is easily fixed. First, a few compelling numbers.

The energy required to produce all foods, from grains to meat, is enormous, about one-quarter of all energy generated, according to a 2018 study in Science. Within that are the greenhouse-gas emissions that escape from decomposing food thrown away each day, amounting to six percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions. As much as 40 percent of food in the U.S. is discarded. That adds up to 40 million tons a year, with each person averaging nearly a pound of food waste each day. Food waste is the single largest component of US landfills. Each American family wastes an average of $1,600 a year on excess food. This needs to change.

MARK STEBNICKI, PEXELS

MARK STEBNICKI, PEXELS

Home Composting Made Easy

Save planet Earth one unused vegetable or spoiled fruit at a time. Use to make more fruits and vegetables. You’re enhancing one of Earth’s grand cycles.

One of many good things about composting is that it is pure good. Another is that it is free—you’ve already paid for it. These alone make composting worthwhile. And then there’s the nickname, “black gold.”

Composting is really a form of self-philanthropy. It imposes on the giver only a little effort, and provides the receiver—often, in an odd twist, also the giver—a valuable substance, the use of which should result in something beautiful, delicious, and healthy, and often all three.

Hence the many compost enthusiasts; it is a wonder there are not many more. Here is a brief guide to getting started in the compost game, followed by a resource if you want to get really serious.

The best reason to compost is to reduce the organic waste you contribute to any one of New York State’s 27 municipal landfills, the nightmare worlds where discarded yard gnomes outnumber humans.

The second best reason is that the black gold you make is really good for plants. Composting duplicates nature’s own decomposition of organic matter but accelerated. The result in both cases is simple compounds (starches, sugars, proteins) that plants can break down further and use to grow and thrive.

Even if you don’t use the compost you make, someone in the neighborhood will gladly take it off your hands. Or scatter it in public gardens and groves—municipal employees rarely have time for such embellishment. (Note: To avoid arrest for suspicious activity, obtain permission.)

KATHY CHOW

KATHY CHOW

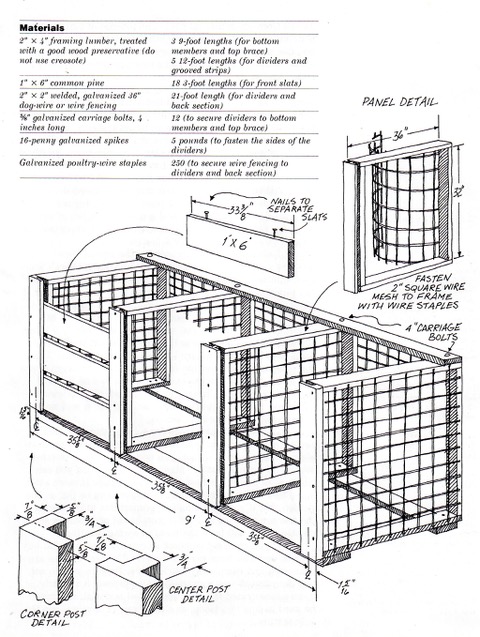

This compost machine will make you the envy of the neighborhood. It’s resurrected from Crocket’s Flower Garden. A disorderly, untended heap will eventually produce compost too, just at an excruciating pace.

The Real Cost Of Plastic Bottles

How A Convenience Became A Calamity. Why Not Reuse?

Early in the 19th century, several spas around the world began selling their waters for their supposed healing powers. New York’s Saratoga Springs is one of the most well-known. The water was marketed as a cure for all manner of things, including hangovers, liver complaints, cancer, diabetes, and even the “weakness of women.” We think there’s a connection.

Water is essential to our bodily health. Most people can only last three days without water. But must we walk around everywhere with a plastic water bottle just to “hydrate” ourselves? What is the real cost?

MAGDA EHLERS, PEXELS

MAGDA EHLERS, PEXELS

We recycle a large percentage of the plastic bottles we buy, but not enough. Let’s reuse instead.

Eating Lower On The Food Chain

We Americans Need To Modify What And How We Eat. We Can Do It!

Most of us were raised under recommendations that we “get plenty of protein.” Protein is a crucial building block in the structure of our cells and the functions our metabolism. For the most part, Americans already get plenty of it, through grains, legumes, some types of animal protein or meat. In fact, Americans eat more meat than just about any other country or culture: about 270 pounds a year on average, in a virtual tie for Australia for second, well behind leader Luxemburg (300 pounds). The world average is 102 pounds.

As farming technology improved, production has gone up, and prices have come down, making animal protein available to more household dinner tables. But the amount we consume far exceeds the human body’s need for protein.

Two Michael Pollan books, Food Rules and Omnivore’s Dilemma

Repair And Reuse

Any Good Thing Is Worth Repairing; Spend Time On Planet Pre-Owned

For centuries, humans repaired and reused everything useful until scarcely a part of the original remained. Only the wealthy discarded what was new. Eventually, driven by economic growth and technological progress, the consumer culture emerged to change all that. It goaded us to trade in the almost new for the brand new. It taunted us if we didn’t have the coolest new toy or wear the season’s hot fashion or know the new dope song. It mocked moderation, rewarded superficiality, and celebrated material excess. It invented the McMansion, the rent-a-jet, the credit default swap, the three-ton SUV, the collateralized debt obligation, the superstar, the superstar-branded sneaker, the superstar-branded totally awesome men’s toiletries line.

The result is mountains of broken, glistening, badly made stuff, most of it derived somehow from petroleum. It’s the product of a culture that’s a toxic mix of misplaced, counterproductive economic growth and a perversion of the American dream that replaces hard work and talent with an implacable sense of entitlement.

TOM PARRETT

TOM PARRETT

Bargain Barn

Packaging

The Packaging Of Products Has Taken On A Life Of Its Own

A few years ago, some women in India got discouraged by the amount of packaging they had to take home when they bought a product. They had colloquy with a store owner, and when no satisfactory response emerged, they simply removed the packaging and left it in the store. Their point was to shift the responsibility of recycling the packaging back to the store owners. People around the world are showing they like being hands-on at the store, and not just health-food rooters. Entire supermarkets in Germany have zero packaging. In New York City, new stores are opening that allow shoppers to fill their own containers with the store’s products. The Marks & Spencer chain in England is experimenting with package-free food.

Currently, when we get most products home, it becomes our job to dispose of the plastic wrapping, the boxes, the bottles that manufacturers and producers use often for their convenience. Hard plastic “clamshells” are the worst. It’s not surprising that recycling numbers are very low—around 14 percent.

WALKER EVANS, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, 1936

WALKER EVANS, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, 1936

Winter Salt

Making Winter Ice Nonskid

Unless scrupulously applied, road salt is a disaster for anything but ice. If you don’t believe us, sprinkle salt in a potted plant, on wet steel, or on concrete over time.

There is no perfect solution for winter’s hazard, and it’s getting worse with climate change. The best – and only – defense is clearing snow early and often. Deicers only work on a thin layer, creating slush that should also be removed before it refreezes. Applying grit is relatively benign though it does clog culverts & storm drains.

For a walk or icy patch of driveway, use sand instead, obtainable in five-pound or ten-pound bags at your hardware store or garden center. It provides a non-slip surface, and being a darker color than snow and ice, it soaks up heat, which melts the ice without harm to plants—not as quickly as salt, which is admittedly speedy, but soon enough. And which would you rather have tracked into your kitchen or place of business, salt or sand?

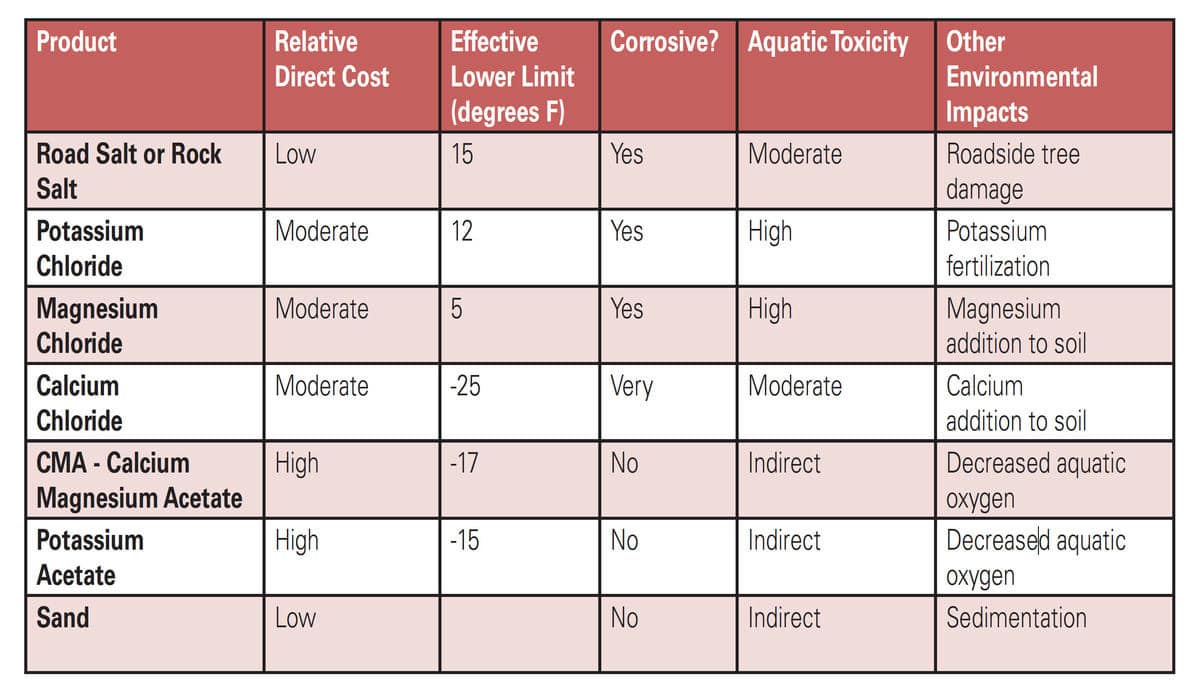

This is the Road Salt comparison chart from the experts at the Cary Institute. Each substance has it’s pros and cons and some are just plain toxic and don’t work. (e.g., the efficacy of “pet-friendly” urea is widely debated and it is a cause of nasty algae blooms). Colder temperatures require different chemicals that have different application rates.

Consider these well-rounded homeowner tips from Cary and find out more about what you can do to ensure you are not overusing road salt which can damage metal and concrete, contaminate drinking water, and harm aquatic plants and animals.

Any sand will do for ice. If there’s no beach handy, try a hardware store or garden center. And keep a bucket of sand in the car in case you or a stranger get stuck.