Provision From Nature

Fish, Fowl, the Four-legged of Hoof and Paw: Yumm

In this area, it’s not realistic to think that you can live entirely off the land unless you are a farmer. But it is practical and reasonable to augment your pantry, freezer, and diet with nature’s bounty and New York State encourages you to do so. You can dine without fear of agribiz additives, but will consume what your meal did so do avoid toxic waste sites and runoff.

Hunting Game: The assortment of animals for which you can obtain a hunting license is still longer than those that are threatened or endangered, and some are so plentiful they are pests. The burrowing groundhog, the munching rabbit, the fleet fox, the scurrilous squirrel, the cagey coyote, the bounding deer—all are legally susceptible to the bullet, the pellet, and the arrow. So too is the ravenous brown bear, more frequent in our area lately, and so easy to shoot it is a shame to call this hunting. But given that the big fellow is so omnivorous he/she/it will help him/her/itself to bird feeders, the contents of a garage freezer, cherished beehives (bears eat the bees, too), and swat a yipping poodle into the next state, perhaps he/she/it has should have avoided the neighborhood.

The magnificent rainbow trout, a great gamefish and excellent eating.

RICH STALZER

RICH STALZER

Preserving Fruits and Vegetables for a Cold and Distant Day

For much of modern history humans have, out of necessity, learned to preserve food. Fish was smoked, salted, and dried and meat much the same. Barley and other grains were fermented into beer, providing much need carbohydrates for hard physical labor. Grapes, apples, and plums were also “preserved” by turning the fruits into wines, cider, and brandies.

Today, in our world, many foods are preserved for us and available at any time of year, yet the preserving of what’s grown can be a rewarding part of being a gardener. And there’s nothing like a midwinter repast of your warm-weather harvest to lift your spirits.

iStock

iStock

Once you master the science of safe canning, your garden’s flavors can be yours year-round.

Support Local Farmers and the Vendors Who Buy from Them

Our food system is starting to come full circle, and it’s about time.

Since World War II, Americans have increasingly relied on Big Ag and the food-processing industry for their food. There have been giant strides in productivity and automation. Consumers have more food choices than ever before. But with that, food has moved farther away from its sources—the land, the barn, the pasture, the lake and river. It has gained all sorts of lab-tweaked ingredients to assure good “mouth feel,” the right sweetness and umami, pleasing color, quantities of manufactured vitamins and minerals, and long shelf life.

There was a backlash, starting with the natural-food, back-to-nature movement in the 1960s, but locally raised food for local kitchens didn’t keep pace until recently—often was not even grown except as a farm-stand sideline.

Fortunately, positive food trends are underway. Small farmers have returned to the fields and are growing more fresh foods every year. Consumers are responding, rewarding farmers at green markets in cities and towns and clamoring for more. Restaurants are adding farm-to-table menu items. New restaurants tend to be predominantly local- and fresh-sourced. (One local chef flies twice-weekly to Cape Cod for fish, oysters, and clams. That’s fresh-sourced.) Even supermarkets have started to feature local fruits and produce. And subscribing to CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) farm shares is becoming standard practice for many local households, which gives farmers income they can plan on.

This area of New York has been farm country since the 18th century. Its excellent growing conditions and soils have produced many generations of successful farmers. With the fading of the local dairy industry in the last quarter century, farmers and landowners have tried everything from Belted Galloway cattle to exotic salad greens. Much of the machinery-farmed land continues in production, growing field corn, hay, grains, and cover crops. But the move toward small-scale sustainable agriculture is taking hold In this area, the farm Moody Hill was a pioneer in the late 1980s, growing organic vegetables using compost from a complementary business that took in cow and horse manure from local farms and food waste from the Culinary Institute in Hyde Park, also branding and bagging it for sale in garden centers. The company now includes a commercial-scale composting operation, a thousand-acre organic farm, a year-round store, restaurant and prepared-food business, and an educational branch.

The future offers solid promise in this direction, especially at the scale of family farms and of local farming groups that pool resources, share distributors to towns and cities, and support local farmers’ markets. The Amish might have something to teach in this regard, as might other models. A meld of age-old community-farming practices, 21st century aids and tools, and government encouragement seems a viable small-farm strategy.

What’s needed is sustainable farming practices, which start with treating the soil as a renewable resource but not with chemical fertilizers: with organic matter and tilth, crop rotation to minimize insects and disease, and cover crops mixed in to restore minerals. Some historic small farms have been practicing sustainability without knowing the term; others, encouraged by county ag advisors, are making the transition without difficulty. After all, it is agribusiness that’s addicted to the spiral of monoculture—fertilizer—insecticides—government price support—consequence-free pollution. We need a huge shift in perspective, starting with a change in allocation of state and federal money from agribusiness stock appreciation to healthy food and food security for all. A good starting point, suggested Ricardo Salvador of the Union of Concerned Scientists and food authority Mark Bittman, to change the name of the $145 billion department that oversees all this, Agriculture, to the Department of Food and Well-being.

Consumers and the planet have much to thank today’s sustainable farmers for, but there is much more to do to bring our farming and food-growing full circle, back to the land.

Use your favorite search engine to learn about these food resources. Many of the farms offer products online. Before visiting a farm, it is best to call ahead.

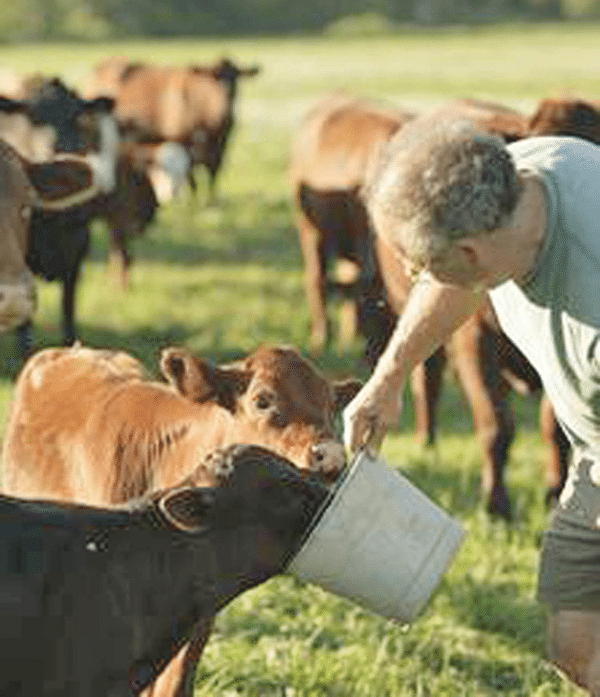

Feeding yearling calves at Whippoorwill Farm on Salmon Kill Road, Salisbury, CT.

The hives of Dennis and Juliette of Remsburger Honey & Maple, Pleasant Valley.

FARMER’S MARKETS

Amenia Farmer’s Market, Amenia

City of Hudson Farmer’s Market, Hudson

Copake-Hillsdale Farmer’s Market, Hillsdale

Milan Farmer’s Market, Red Hook

Millerton Farmer’s Market, Millerton

Pine Plains Farmers Market, Pine Plains

Philmont Farmer’s Market, Philmont

CSA FARM SHARES

Adamah CSA, Falls Village, CT

Common Hands Farm, Hudson

Empire Farm, Copake

Full Circus Farm, Pine Plains

Hawk Dance Farm, Hillsdale

Herondale Farm, Ancramdale

Maitri Farm, Amenia

Moon In The Pond Farm and Farm Education, Inc. Sheffield, MA

Olde Forge Farms, Wassaic

Otero Family Farm, Stanfordville

Rocksteady Farm & Flowers, Millerton

Sisters Hill Farm, Standfordville

Wassaic Community Farm, Wassaic

FAMILY FARMS

Arch Bridge Farm, Ghent

Brookby Farm Store & Dairy, Dover Plains

Cagneys Way Farm, Stanfordville

Chaseholm Farm, Pine Plains

Copper Star Alpaca Farm, Millerton

Cowberry Crossing Farm, Claverack

Cream Hill Veal, West Cornwall, CT

Daisy Hill Farm, Millerton

Darlin’ Doe Farm, Germantown

Dashing Star Farm, Millerton

Dirty Dog Farm, Germantown

Double Decker Farm, Hillsdale

Edible Sunshine, Philmont

Elk Ravine Farm, Amenia

Field Apothecary & Herb Farm, Germantown

Flowering Heart, Philmont

Great Song Farm, Red Hook

Green Owl Garlic, Rhinebeck

Hawthorne Valley Farm, Ghent

Hearty Roots Community Farm, Germantown

JSK Cattle Company, Millbrook

Katchkie Farm, Kinderoook

Kerley Homestead Farm, Red Hook

Letterbox Farm Collective, Hudson

Lilly Moore Farm, Pleasant Valley

Lineage Farm, Hudson

Marshmeadow Farm, Germantown

Mead Orchards, Tivoli

Meili Farm, Amenia

MX Morningstar Farm, Hudson

Nannick Farms, Red Hook

New York Beef Company, Poughkeepsie

Northwind Farms, Tivoli

Perry Hill Farm, Millbrook

Pigasso Farms, Copake

Point of View Farm, Standfordville

Remsburger Honey & Maple, Pleasant Valley

Red Fern Farm, Clermont

Rocky Fresh, Hudson

Samascott Orchards, Kinderhook

Roxbury Farm, Kinderhook

Second Chance Farm, Rhinebeck

Silamar Farm, Millerton

Slow Fox Farm, Rhinebeck

Smokey Hollow Farm, Ghent

Sol Flower Farm, Millerton

Starling Yards, Red Hook

Ten Barn Farm, Ghent

Ten Mile River Poultry, Wingdale

Threshold Farm, Philmont

Thunderhill Farm, Stanfordville

Turtle Tree Seed, Copake

VIDA Farm, Ghent

Walbridge Farm Market, Millbrook

Whippoorwill Farm, Salisbury, CT

Wild Hive Grain Project, Clinton Corners

Willow Brook Farm, Millerton

Zfarms, Dover Plains

SOURCE: localharvest.org

If these lists contain an error or have omitted a farm, please let us know.