Climate Crisis

The coming climate emergency is here

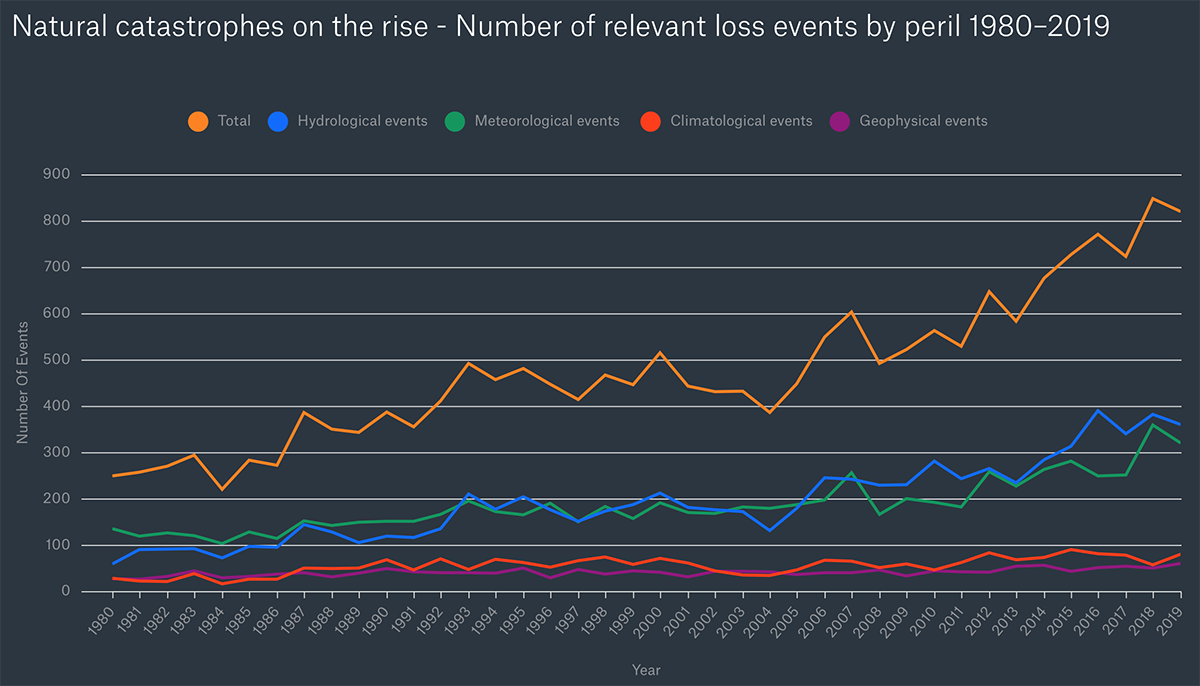

We are colliding with a future of extremes. We base all our choices about risk management on what’s occurred in the past, and that’s no longer a safe guide.

—Alice Hill, senior fellow for climate change policy, Council on Foreign Relations, 1-21-20

By now, two-thirds of Americans give some credence to global warming, or to use a more accurate term, climate chaos. They are aware it is a threat to our “way of life.” They want their elected officials to do something about it.

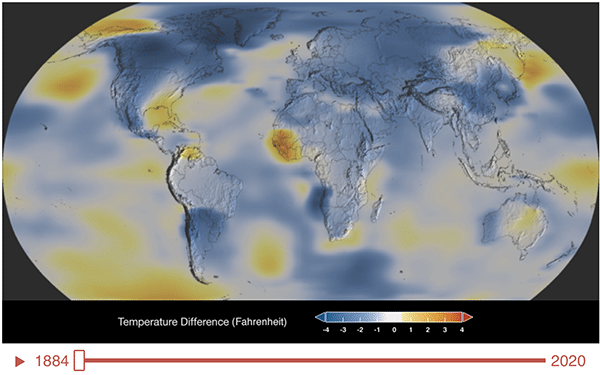

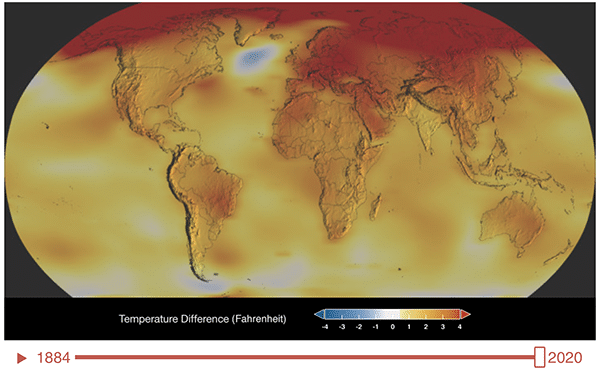

What science has been promising since the early 1980s, and hinting at since the 1880s—a more tumultuous and dangerous climate—is crowding the edge of our reality. We should no longer speak of it in the future tense.

And now that for the moment at least rational leaders are back in charge of the American enterprise, the true battle to save the evolved life of our planet, what’s left of the natural world we have so carelessly and wantonly exploited, and the biodiversity we fundamentally depend on, must re-commence, with not a moment to waste.

Fortunately, we know in the short term what must be done. We must dramatically reduce, each and every one of us, the carbon we release into our air. The first goal as a species is net zero, meaning we stop making it any worse. We start by doing so as individuals. Then collectively we have to wring enough carbon out of the air to restore some semblance of order. The storms have to get smaller and briefer. The flooding and wildfires have to be rare again. The coral reefs, great source of much of the ocean’s life, need to regrow what has been lost to heat bleaching and acidification. We broke it, we have to fix it.

North East / Millerton and New York State Join Forces

New York is among the leading states in the nation to address global warming. It has codified into law ambitious deadlines for achieving net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050, starting with carbon-free (no fossil fuels) grid electricity by 2040.

Our State has backed up this rigorous schedule with well-thought-out programs and generous financial incentives so even small communities across the state can mitigate climate change locally, adapt to rising temperatures and more severe weather, and make themselves sturdily climate resilient.

Here are two state programs our community has embraced – the Task Force is tasked with coordinating them.

Mitigation and Resilience

Three Serious Approaches to Our Climate Crisis, with Varying Emphases on Mitigation and Resilience

“We basically have three choices: mitigation, adaptation, and suffering. We’re going to do some of each. The question is what the mix is going to be.”

John Holdren, author of this stark assessment, is a chaired professor of the Harvard Kennedy School, has been a top science advisor to Presidents Obama and Clinton, head of Woods Hole Research Center, and began his career as a theoretical physicist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Not many have the benefit of Holdren’s grasp of the fullness of our climate crisis. And while more people are coming around to the idea that we must do something—or the government must do something—enough skepticism and outright climate denial remains that this situation itself has become a big research topic.